User:Thadh/a

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

Abau • Afar • Albanian • Ama • Anguthimri • Aragonese • Asturian • Bambara • Bavarian • Belizean Creole • Big Nambas • Breton • Cameroon Pidgin • Catalan • Chayuco Mixtec • Chibcha • Choctaw • Chuukese • Cimbrian • Coatepec Nahuatl • Cora • Cornish • Corsican • Czech • Dalmatian • Danish • Dutch • Egyptian • Emilian • Estonian • Fala • Finnish • Franco-Provençal • French • Fula • Galician • German • Gilbertese • Gothic • Grass Koiari • Gun • Haitian Creole • Hawaiian • Hokkien • Hungarian • Ido • Igbo • Indo-Portuguese • Ingrian • Interlingua • Inupiaq • Irish • Istriot • Italian • Jamaican Creole • Japanese • K'iche' • Kabyle • Kalasha • Kapampangan • Kari'na • Kashubian • Koitabu • Krisa • Ladin • Lashi • Latgalian • Latin • Laz • Ligurian • Louisiana Creole • Lower Sorbian • Malay • Mandarin • Mandinka • Maori • Mezquital Otomi • Middle Dutch • Middle English • Middle French • Middle Welsh • Mòcheno • Mopan Maya • Mountain Koiari • Murui Huitoto • Nauruan • Neapolitan • Nias • Norman • Norwegian Bokmål • Norwegian Nynorsk • Nupe • Occitan • Old Czech • Old Danish • Old Dutch • Old English • Old French • Old Galician-Portuguese • Old Irish • Old Polish • Old Swedish • Omaha-Ponca • Ometepec Nahuatl • Palauan • Papiamentu • Polish • Portuguese • Rapa Nui • Rawang • Romagnol • Romani • Romanian • Sardinian • Sassarese • Satawalese • Scots • Scottish Gaelic • Serbo-Croatian • Sicilian • Silesian • Skolt Sami • Slovak • Slovene • Slovincian • Spanish • Sranan Tongo • Sumerian • Swahili • Swedish • Tagalog • Tarantino • Tày • Tok Pisin • Tokelauan • Tooro • Tyap • Upper Sorbian • Vietnamese • Votic • Walloon • Welsh • West Makian • Yola • Yoruba • Yucatec Maya • Zazaki • Zhuang • Zou

Page categories

Translingual

Etymology 1

![]() Modification of capital A.

Modification of capital A.

Pronunciation

Letter

a (upper case A)

- The first letter of the basic modern Latin alphabet.

- (superscript) See ª.

Symbol

a

- (IPA, phonetics) an open front or central unrounded vowel.

- (IPA, superscript ⟨ᵃ⟩) -coloring or a weak, fleeting, epenthetic or echo .

- (international standards) transliterates Indic अ (or equivalent).

See also

- For more variations, see Appendix:Variations of "a".

Further reading

a on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

a on Wikipedia.Wikipedia  open front unrounded vowel on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

open front unrounded vowel on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

Etymology 2

Abbreviation of atto-, from Danish atten (“eighteen”).

Symbol

a

- atto-, prefix for 10-18 in the International System of Units.

Etymology 3

Symbol

a

- Year as a unit of time, specifically a Julian year or 365.25 days.

Etymology 4

Abbreviation of are, from French are.

Symbol

a

Etymology 5

Abbreviation of English acceleration.

Symbol

a

Etymology 6

(This etymology is missing or incomplete. Please add to it, or discuss it at the Etymology scriptorium. Particularly: “from annuity?”)

Symbol

a

- (actuarial notation) Annuity; (specifically) annuity-immediate.

- ax:n̅| ― n-year annuity-immediate to a person currently age x

- ax ― life annuity-immediate to a person currently age x

Character=A1Please see Module:checkparams for help with this warning.

Other representations of A:

Gallery

- Letter styles

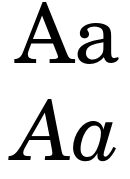

-

Uppercase and lowercase versions of A, in normal and italic type

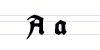

-

Uppercase and lowercase A in Fraktur

-

Approximate form of Greek uppercase Α (a, “alpha”), the source of both common variants of a A in uncial script

English

Etymology 1

From Middle English a, an, from Old English ān (“one; a; lone; sole”). More at one. The "n" was gradually lost before consonants in almost all dialects by the 15th century. Cognate with Alemannic German a (“a, an”), East Franconian a (“a, an”).

Pronunciation

- (stressed) IPA(key): /ˈeɪ/

- (unstressed) IPA(key): /ə/

Audio (US, stressed form): (file) Audio (US, unstressed form): (file) - Rhymes: -eɪ, -ə

- Homophone: her (non-rhotic, unstressed)

Article

a (indefinite)

- One; any indefinite example of. [1]

- There was a man here looking for you yesterday.

- 1992, Rudolf M Schuster, The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North America: East of the Hundredth Meridian, volume V, Chicago, Ill.: Field Museum of Natural History, →ISBN, page vii:

- With fresh material, taxonomic conclusions are leavened by recognition that the material examined reflects the site it occupied; a herbarium packet gives one only a small fraction of the data desirable for sound conclusions. Herbarium material does not, indeed, allow one to extrapolate safely: what you see is what you get […]

- 2005, Emily Kingsley (lyricist), Kevin Clash (voice actor), “A Cookie is a Sometime Food”, Sesame Street, season 36, Sesame Workshop:

- Hoots the Owl: Yes a, fruit, is a , any, time, food!

- 2016, VOA Learning English (public domain)

- One; used before score, dozen, hundred, thousand, million, etc.

- I've seen it happen a hundred times.

- Used in some phrases denoting quantity, such as a few, a good many, a couple, a little (for an uncountable noun), etc.

- They asked me a few questions.

- Used in some adverbial phrases denoting degree or extent, such as a little, a bit, a lot, etc.

- The door was opened a little.

- The same; one and the same. Used in phrases such as of a kind, birds of a feather, etc.

- We are of a mind on matters of morals.

- They're two of a kind.

- Any; every; used before a noun which has become modified to limit its scope.[2]

- A man who dies intestate leaves his children troubles and difficulties.

- Any; used with a negative to indicate not a single one.[3]

- It was so dark that we couldn't see a thing.

- He fell all that way, and hasn't a bump on his head?

- Used before an adjective that modifies a noun (singular or plural) delimited by a numeral.

- a staggering three million dollars

- The holidays are a mere one week away.

- One; someone named; used before a person's name, suggesting that the speaker knows little about the person other than the name.[4]

- We've received an interesting letter from a Mrs. Miggins of London.

- Used before an adjective modifying a person's name.

- 2018, “Rwandan court drops all charges against opposition figure”, in Associated Press:

- "I will continue my campaign to fight for the rights of all Rwandans," a surprised but happy Rwigara told reporters after celebrating.

- Someone or something like; similar to;[3] Used before a proper noun to create an example out of it.

- The center of the village was becoming a Times Square.

- The man is a regular Romeo.

Usage notes

- In standard English, the article a is used before consonant sounds, while an is used before vowel sounds; for more, see the usage notes about an.

Derived terms

Translations

See also

Etymology 2

- From Middle English a, o, from Old English a-, an, on.

- Unstressed form of on.

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- To do with separation; In, into. [1]

- Torn a pieces.

- To do with time; Each, per, in, on, by. Often occurs between two nouns, where the first noun occurs at the end of a verbal phrase.[1]

- I brush my teeth twice a day.

- c. 1599–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio), London: Isaac Iaggard, and Ed Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, :

- A Sundays

- 2019 February 3, “UN Study: China, US, Japan Lead World AI Development”, in Voice of America, archived from the original on 7 February 2019:

- Patent requests for machine learning activities grew on average by 28 percent a year between 2013 and 2016, the study found.

- To do with status; In. [1]

- King James Bible (II Chronicles 2:18)

- To set the people a worke.

- King James Bible (II Chronicles 2:18)

- (archaic) To do with position or direction; In, on, at, by, towards, onto. [1]

- Stand a tiptoe.

- (archaic) To do with process, with a passive verb; In the course of, experiencing. [1]

- 1964, Bob Dylan (lyrics and music), “The Times They Are a-Changin'”:

- The times, they are a-changin'.

- (archaic) To do with an action, an active verb; Engaged in. [1]

- c. 1608–1609 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedy of Coriolanus”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio), London: Isaac Iaggard, and Ed Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, :

- It was a doing.

- 1611, The Holy Bible, (King James Version), London: Robert Barker, , →OCLC, Hebrews 11:21:

- Jacob, when he was a dying

- (archaic) To do with an action/movement; To, into. [1]

- (obsolete) To do with method; In, with. [1]

- c. 1589–1590 (date written), Christopher Marlo, edited by Tho Heywood, The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Iew of Malta. , London: I B for Nicholas Vavasour, , published 1633, →OCLC, (please specify the page):

- Stands here a purpose.

- (obsolete) To do with role or capacity; In. [1]

Usage notes

- (position, direction): Can also be attached without a hyphen, as aback, ahorse, afoot. See a-

- (separation): Can also be attached without hyphen, as asunder. See a-

- (status): Can also be attached without hyphen, as afloat, awake. See a-.

- (process): Can also be attached with or without hyphen, as a-changing

See also

Etymology 3

From Middle English a, ha contraction of have, or haven.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Verb

a

- (archaic or slang) Have.

- I'd a come, if you'd a asked.

- 1884, Robert Holland, M.R.A.C., A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Chester, volume Part I--A to F., London: English Dialect Society, page 1:

- Oi'd a gen im a clout, if oi'd been theer.

- c. 1599–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio), London: Isaac Iaggard, and Ed Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, (please specify the act number in uppercase Roman numerals, and the scene number in lowercase Roman numerals):

- So would I a done by yonder ſunne

?And thou hadſt not come to my bed.

Usage notes

- Now often attached to preceding auxiliary verb. See -a.

Derived terms

Etymology 4

From Middle English a, a reduced form of he (“he”)/ha (“he”), heo (“she”)/ha (“she”), ha (“it”), and hie, hie (“they”).

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ə/

- (it): (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ə/, /ɑ/

- Rhymes: -ə, -ɑ

Pronoun

a

- (obsolete outside England and Scotland dialects) He, she, they: the third-person singular or plural nominative.[4]

- 1855, Kingsley, W. Ho!, page 120 (edition of 1889):

- He've a got a great venture on hand, but what a be he tell'th no man.

- 1864, Tennyson, N. Farmer, Old Style, st. 2:

- Doctors, they knaws nowt, fur a says what's nawways true.

- (obsolete outside England and Scotland dialects) He, the third-person singular nominative.

- 1598–1599 (first performance), William Shakespeare, “Much Adoe about Nothing”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio), London: Isaac Iaggard, and Ed Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, :

- a’ brushes his hat o’ mornings.

- 1795, Peter Pindar, The Royal Visit to Exeter, a Political Epistle: by John Ploughshare ... published by Peter Pindar, Esq, page 5:

- Well! in a come [in he came]—KING GEORGE to town, / With doust and zweat az netmeg brown, / The hosses all in smoke;

- 1860, Kite, Sng. Sol., ii, 16:

- A do veed amang th' lilies.

- 1864, Tennyson, N. Farmer, Old Style, st. 7, version of 1917, Raymond Macdonald Alden, Alfred Tennyson, how to Know Him, page 226:

- "The amoighty's a taakin' o' you to 'issén, my friend," a said,

- (obsolete outside England and Scotland dialects) She, the third-person singular nominative.

- 1790, Grose, MS. add. (M.):

- A wanted me to go with her.

- 1876, Bound, Prov.:

- Did a do it!

- 1883, Hardy, Tover, page 124 (edition of 1895):

- A's getting wambling on her pins .

- 1790, Grose, MS. add. (M.):

- 1855, Kingsley, W. Ho!, page 120 (edition of 1889):

Etymology 5

From Middle English of, with apocope of the final f and vowel reduction.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- (archaic or slang) Of.

- The name of John a Gaunt.

- c. 1597 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The First Part of Henry the Fourth, ”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (First Folio), London: Isaac Iaggard, and Ed Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, :

- What time a day is it?

- 1598, Beniamin Ionson [i.e., Ben Jonson], “Euery Man in His Humour. A Comœdie. ”, in The Workes of Beniamin Ionson (First Folio), London: Will Stansby, published 1616, →OCLC, (please specify the act number in uppercase Roman numerals, and the scene number in lowercase Roman numerals):

- It’s six a clock.

- 1931, A. P. Carter, "When I'm Gone":

- Two bottles 'a whiskey for the way

- 2006, Noire , Thug-A-Licious: An Urban Erotic Tale, New York, N.Y.: One World, Ballantine Books, →ISBN, page 152:

- Isis rode my mug like she was on a ten-inch dick, and as soon as she nutted I tossed her ass off a me and flipped her on her back, then fucked the shit outta her cause it was payback time.

Usage notes

- Often attached without a hyphen to preceding word.

Etymology 6

From Northern Middle English aw, alteration of all.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ɔ/

- Rhymes: -ɔ

Adverb

a (not comparable)

Adjective

a (not comparable)

Etymology 7

Symbols

Symbol

a

- Distance from leading edge to aerodynamic center.

- specific absorption coefficient

- specific rotation

- allele (recessive)

Etymology 8

Adverb

a

- (crosswords) across

- Do you have the answer for 23a?

- (chiefly US) Alternative spelling of a.m. (“ante meridiem”) or am

Etymology 9

Particle

a

- Alternative form of -a (“empty syllable added to songs, poetry, verse and other speech”)

- 2001, Louis F. Newcomb, Car Salesman: A Legacy, iUniverse (→ISBN), page 91:

- “I show a you right a here I can fuck a you.” “Is she crazy?” I asked Wyman.

- 2001, Louis F. Newcomb, Car Salesman: A Legacy, iUniverse (→ISBN), page 91:

Etymology 10

Interjection

a

- ah; er (sound of hesitation)

- 1847 January – 1848 July, William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair , London: Bradbury and Evans , published 1848, →OCLC:

- "We will resume yesterday's discourse, young ladies," said he, "and you shall each read a page by turns; so that Miss a—Miss Short may have an opportunity of hearing you"; and the poor girls began to spell a long dismal sermon delivered at Bethesda Chapel, Liverpool, on behalf of the mission for the Chickasaw Indians.

Etymology 13

Abbreviations.

- (stenoscript) the word a.m.

- (stenoscript) the prefix ad-.

Quotations

Additional quotations for any terms on this page may be found at Citations:a.

References

- Lesley Brown, editor-in-chief, William R. Trumble and Angus Stevenson, editors (2002), “Thadh/a”, in The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles, 5th edition, Oxford, New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, →ISBN, page 1.

- Philip Babcock Gove (editor), Webster's Third International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (G. & C. Merriam Co., 1976 , →ISBN)

- “a” in Christine A. Lindberg, editor, The Oxford College Dictionary, 2nd edition, New York, N.Y.: Spark Publishing, 2002, →ISBN, page 1.

- “a, adj.”, in OED Online

, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Further reading

- “Thadh/a”, in OneLook Dictionary Search.

- “Thadh/a”, in Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary, Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam, 1913, →OCLC.

Abau

Pronunciation

Noun

a

Afar

Pronunciation

Determiner

á

Derived terms

See also

See Template:aa-demonstrative determiners.

References

- E. M. Parker, R. J. Hayward (1985) “a”, in An Afar-English-French dictionary (with Grammatical Notes in English), University of London, →ISBN

- Mohamed Hassan Kamil (2015) L’afar: description grammaticale d’une langue couchitique (Djibouti, Erythrée et Ethiopie), Paris: Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (doctoral thesis)

Albanian

Etymology 1

- According to Orel, the particle and conjunction are etymologically identical. From Proto-Albanian *a and cognate to Ancient Greek ἦ (ê, “indeed”).[1]

- From Proto-Albanian *(h)au, from Proto-Indo-European *h₂eu- (“that”). Cognate to Ancient Greek αὖ (aû, “on the other hand, again”). A proclitic disjunctive particle, used with one or more parts of the sentence.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a

Etymology 2

From Proto-Albanian *(h)an, from Proto-Indo-European *h₂en (“there”). Cognate with Latin an (“yes, perhaps”). Interrogative particle, usually used proclitically in simple sentences.

Pronunciation

Particle

a

References

- ^ Orel, Vladimir E. (1998) “a part. ('whether'), conj. ('or')”, in Albanian Etymological Dictionary, Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill, →ISBN, page 1

- ^ Mann, S. E. (1948) “Thadh/a”, in An Historical Albanian–English Dictionary, London: Longmans, Green & Co., page 1

Further reading

- “Thadh/a”, in FGJSSH: Fjalor i gjuhës së sotme shqipe [Dictionary of the modern Albanian language] (in Albanian), 1980

- “Thadh/a”, in FGJSH: Fjalor i gjuhës shqipe [Dictionary of the Albanian language] (in Albanian), 2006

Ama

Pronunciation

Noun

a

Anguthimri

Verb

a

- (transitive, Mpakwithi) to pull

References

- Terry Crowley, The Mpakwithi dialect of Anguthimri (1981), page 184

Aragonese

Etymology

Article

a f sg

- the

- a luenga aragonesa ― the Aragonese language

Asturian

Etymology

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

Derived terms

Bambara

Article

a

- the (definite article).

Interjection

a

Pronoun

a

Synonyms

- (they): u

Bavarian

Etymology 1

Cognate with German ein, eine, Yiddish אַ (a), אַן (an).

Pronunciation

Article

a

See also

| m | n | f | pl | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stressed | unstressed | stressed | unstressed | stressed | unstressed | stressed | unstressed | ||

| definite | nominative | der, da | — | das, es, des | 's | de | d' | de | d' |

| accusative | en, den | 'n | |||||||

| dative | em, dem | 'm | em, dem | 'm | der, da | — | |||

| genitive1 | des | des | der, da | der, da | |||||

| indefinite | nominative | a | — | a | — | a | — | ||

| accusative | an | 'n | |||||||

| dative | am | 'm | am | 'm | a, ana | 'na | |||

- oa (“one”, determiner)

Etymology 2

Unstressed form of ea

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a

- he

See also

| nominative | accusative | dative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stressed | unstressed | stressed | unstressed | stressed | unstressed | ||

| 1st person singular | i | — | mi | — | mia (mir) | ma | |

| 2nd person singular (informal) |

du | — | di | — | dia (dir) | da | |

| 2nd person singular (formal) |

Sie | — | Eahna | — | Eahna | — | |

| 3rd person singular | m | er | a | eahm | 'n | eahm | 'n |

| n | es, des | 's | des | 's | |||

| f | se, de | 's | se | 's | ihr | — | |

| 1st person plural | mia (mir) | ma | uns | — | uns | — | |

| 2nd person plural | eß, ihr | — | enk, eich | — | enk, eich | — | |

| 3rd person plural | se | 's | eahna | — | eahna | — | |

Etymology 3

Adverb

a

Belizean Creole

Preposition

a

References

- Crosbie, Paul, ed. (2007), Kriol-Inglish Dikshineri: English-Kriol Dictionary. Belize City: Belize Kriol Project, p. 19.

Big Nambas

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

References

- Big Nambas Grammar Pacific Linguistics - G.J. Fox

Breton

Etymology 1

From Proto-Brythonic *o, from Proto-Indo-European *h₂pó.

Pronunciation

Preposition

a (triggers soft mutation)

- from (expresses origin)

- tud a Vrest ― people from Brest

- of (indicates an amount)

- un tamm brav a gig ― a nice piece of meat

- of (expresses a quality)

- ur plac’h a enor ― a girl of honour

- after certain adjectives or adverbs expressing quantity

- ur voutailh leun a sistr ― a bottle full of cider

- after ordinal numbers with a plural noun

- tri a vugale ― three children

- used in negative sentences with the grammatical object

- nʼem eus ket ken a vutun ― I donʼt have any more tobacco

- before the infinitive after certain verbs like paouez, mirout, diwall, c'hwitañ

- paouezet eo ar glav a gouezhañ ― it has stopped raining

- after substantivized adjectives used as nouns

- ur vrav a blacʼh ― a pretty girl

- combined with a personal pronoun

- gwelet em boa acʼhanout ― I saw you

- an den a gomzan anezhañ ― the man Iʼm talking about

Inflection

Etymology 2

Pronunciation

Particle

a (triggers soft mutation)

- preverbal particle used when

- the subject precedes the verb

- ar mor a zo glas ― the sea is blue

- the object precedes the verb

- an den-se a glevan ― I hear that man

- the subject precedes the verb

Pronoun

a (triggers soft mutation)

- (relative) that, which, who (used in 'direct' relative clauses, i.e. where the pronoun refers to the subject or the direct object of an inflected verb)

- an hini a garan ― the one whom I love

Cameroon Pidgin

Pronoun

a

- Alternative spelling of I (“1st person singular subject personal pronoun”)

Catalan

Etymology

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- in, at; indicating a particular time or place

- Sóc a Barcelona.

- I am in Barcelona.

- to; indicating movement towards a particular place

- Vaig a Barcelona.

- I'm going to Barcelona.

- to; indicating a target or indirect object

- Escric una carta a la meva àvia.

- I'm writing my grandmother a letter.

- per

- by

- dia a dia.

- day by day.

Usage notes

- When the preposition a is followed by a masculine definite article, el or els, it is contracted with it to the forms al and als respectively. If el would be elided to the form l’ because it is before a word beginning with a vowel, the elision to a l’ takes precedence over contracting to al.

The same occurs with the salat article es, to form as except where es would be elided to s’.

Derived terms

Chayuco Mixtec

Etymology

(This etymology is missing or incomplete. Please add to it, or discuss it at the Etymology scriptorium.)

Conjunction

a

References

- Pensinger, Brenda J. (1974) Diccionario mixteco-español, español-mixteco (Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas “Mariano Silva y Aceves”; 18) (in Spanish), México, D.F.: El Instituto Lingüístico de Verano en coordinación con la Secretaría de Educación Pública a través de la Dirección General de Educación Extraescolar en el Medio Indígena, pages 3, 110

Chibcha

Pronunciation

Noun

a

References

- Gómez Aldana D. F., Análisis morfológico del Vocabulario 158 de la Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia. Grupo de Investigación Muysccubun. 2013.

Choctaw

Conjunction

a

Chuukese

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a

Adjective

a

- he is

- she is

- it is

Related terms

| Present and past tense | Negative tense | Future | Negative future | Distant future | Negative determinate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | First person | ua | use | upwe | usap | upwap | ute |

| Second person | ka, ke | kose, kese | kopwe, kepwe | kosap, kesap | kopwap, kepwap | kote, kete | |

| Third person | a | ese | epwe | esap | epwap | ete | |

| Plural | First person | aua (exclusive) sia (inclusive) |

ause (exclusive) sise (inclusive) |

aupwe (exclusive) sipwe (inclusive) |

ausap (exclusive) sisap (inclusive) |

aupwap (exclusive) sipwap (inclusive) |

aute (exclusive) site (inclusive) |

| Second person | oua | ouse | oupwe | ousap | oupwap | oute | |

| Third person | ra, re | rese | repwe | resap | repwap | rete |

Cimbrian

Alternative forms

- an (Sette Comuni)

Etymology

From Middle High German ein, from Old High German ein, from Proto-West Germanic *ain.

Article

a (oblique masculine an)

References

- Patuzzi, Umberto, ed., (2013) Luserna / Lusérn: Le nostre parole / Ünsarne börtar / Unsere Wörter , Luserna, Italy: Comitato unitario delle isole linguistiche storiche germaniche in Italia / Einheitskomitee der historischen deutschen Sprachinseln in Italien

Coatepec Nahuatl

Noun

a

Cora

Particle

a

- outside

- out of view (from the speaker)

- entering a shallow domain; entering a domain in a shallow or restricted manner

- atyásuuna káasu hece

- The water is pouring into the (shallow) pan.

Antonyms

- u (“inside; within view”)

References

- Eugene Casad, Ronald Langacker (1985) “'Inside' and 'outside' in Cora grammar”, in International Journal of American Linguistics

Cornish

Etymology 1

Onomatopoeic

Pronunciation

Interjection

a

Etymology 2

Pronunciation

Particle

a (triggers soft mutation)

- Inserted before the verb when a subject or direct object precedes the verb

Etymology 3

From Proto-Brythonic *o, from Proto-Celtic *ɸo, from Proto-Indo-European *h₂pó.

Pronunciation

Preposition

a (triggers soft mutation)

- of (expressing separation, origin, composition/substance or a quality)

- of (between a preceding large number and a following plural noun to express quantity)

- from (indicating provenance)

Inflection

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | ahanaf | ahanan |

| Second person | ahanas | ahanowgh |

| Third person | anodho (m) anedhy (f) |

anodhans, anedha |

Corsican

Etymology

From the earlier la.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /ˈa/

- Homophones: à, hà

Article

a f (masculine u, masculine plural i, feminine plural e)

- the (feminine)

Usage notes

- Before a vowel, a turns into l'

Pronoun

a f

Usage notes

- Before a vowel, a turns into l'

See also

References

- “Thadh/a” in INFCOR: Banca di dati di a lingua corsa

Czech

Etymology

Inherited from Old Czech a, from Proto-Slavic *a, from Proto-Balto-Slavic *ō.

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a

Further reading

- “Thadh/a”, in Příruční slovník jazyka českého (in Czech), 1935–1957

- “Thadh/a”, in Slovník spisovného jazyka českého (in Czech), 1960–1971, 1989

Dalmatian

Etymology

Preposition

a

Danish

Etymology 1

Alternative forms

- à (unofficial but common)

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

Etymology 2

Pronunciation

Verb

a

- imperative of ae

Dutch

Etymology 1

From Middle Dutch â, from Old Dutch ā, from Proto-Germanic *ahwō.

Alternative forms

Noun

a f (plural a's, diminutive aatje)

Related terms

Further reading

Aa (waternaam) on the Dutch Wikipedia.Wikipedia nl

Aa (waternaam) on the Dutch Wikipedia.Wikipedia nl

Etymology 2

From Middle Dutch jou, from Old Dutch *jū, a northern (Frisian?) variant of *iu, from Proto-Germanic *iwwiz, a West Germanic variant of *izwiz. Doublet of u.

Pronoun

a

Synonyms

Egyptian

Romanization

a

Emilian

Etymology

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a (personal, nominative case)

Alternative forms

Related terms

| Number | Person | Gender | Disjunctive (tonic) |

Nominative (subject) |

Accusative (direct complement) |

Dative (indirect complement) |

Reflexive (-self) |

Comitative (with) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | First | — | mè | a | me | mêg | ||

| Second | — | tè | et | te | têg | |||

| Third | Masculine | ló | al | ge | se | sêg | ||

| Feminine | lê | la | ||||||

| Plural | First | Masculine | nuēter | a | se | nōsk | ||

| Feminine | nuētri | |||||||

| Second | Masculine | vuēter | a | ve | vōsk | |||

| Feminine | vuētri | |||||||

| Third | Masculine | lôr | i | ge | se | sêg | ||

| Feminine | el | li | ||||||

Estonian

Etymology 1

Clipping of aga. Probably influenced by Russian а (a).

Conjunction

a

- (colloquial, in fast speech) but

Etymology 2

Noun

a

- Abbreviation of aasta.

- Abbreviation of aar.

References

- Thadh/a in Sõnaveeb (Eesti Keele Instituut)

- “Thadh/a”, in Eesti keele seletav sõnaraamat [Descriptive Dictionary of the Estonian Language] (in Estonian) (online version), Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus (Estonian Language Foundation), 2009

Fala

Etymology 1

From Old Galician-Portuguese á, from Latin illa (“that”).

Article

a f sg (plural as, masculine u or o, masculine plural us or os)

- Feminine singular definite article; the

- 2000, Domingo Frades Gaspar, Vamus a falal: Notas pâ coñocel y platical en nosa fala, Editora regional da Extremadura, Chapter 1: Lengua Española:

- A grandeda da lengua española é indiscotibli, i sei estudio, utilización defensa debin sel algo consostancial a nos, […]

- The greatness of the Spanish language is unquestionable, and its study, use and defense must be something consubstantial to us,

Pronoun

a

- Third person singular feminine accusative pronoun; her

See also

| nominative | dative | accusative | disjunctive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first person | singular | ei | me, -mi | mi | ||

| plural | common | nos | musL nusLV nos, -nusM |

nos | ||

| masculine | noshotrusM | noshotrusM | ||||

| feminine | noshotrasM | noshotrasM | ||||

| second person | singular | tú | te, -ti | ti | ||

| plural | common | vos | vusLV vos, -vusM |

vos | ||

| masculine | voshotrusM | voshotrusM | ||||

| feminine | voshotrasM | voshotrasM | ||||

| third person | singular | masculine | el | le, -li | uLV, oM | el |

| feminine | ela | a | ela | |||

| plural | masculine | elis | usLV, osM | elis | ||

| feminine | elas | as | elas | |||

| reflexive | — | se, -si | sí | |||

Etymology 2

From Old Galician-Portuguese a, from Latin ad (“to”).

Preposition

a

- to

- 2000, Domingo Frades Gaspar, Vamus a falal: Notas pâ coñocel y platical en nosa fala, Editora regional da Extremadura, Chapter 1: Lengua Española:

- A grandeda da lengua española é indiscotibli, i sei estudio, utilización defensa debin sel algo consostancial a nos, […]

- The greatness of the Spanish language is unquestionable, and its study, use and defense must be something consubstantial to us,

References

- Valeš, Miroslav (2021) Diccionariu de A Fala: lagarteiru, mañegu, valverdeñu (web), 2nd edition, Minde, Portugal: CIDLeS, published 2022, →ISBN

Finnish

Etymology

Noun

a

Usage notes

Capitalized for the great octave or any octave below that, or in names of major keys; not capitalized for the small octave or any octave above that, or in names of minor keys.

Declension

|

Derived terms

Franco-Provençal

Etymology

Pronoun

a (ORB)

Derived terms

References

- à in DicoFranPro: Dictionnaire Français/Francoprovençal – on dicofranpro.llm.umontreal.ca

- Thadh/a in Lo trèsor Arpitan – on arpitan.eu

French

Etymology 1

Quebec eye-dialect spelling of elle.

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a f

- (Quebec, colloquial) alternative form of elle (“she”)

- C’te fille-là, a’a l’air cute.

- That girl, she looks cute.

Etymology 2

From Old French a, at from Vulgar Latin *at, from Latin habet.

Pronunciation

Verb

a

- third-person singular present indicative of avoir

- Elle a un chat.

- She has a cat.

See also

Further reading

- “Thadh/a”, in Trésor de la langue française informatisé , 2012.

Fula

Etymology 1

Pronoun

a

- you (second person singular subject pronoun; short form)

Usage notes

- Common to all varieties of Fula (Fulfulde / Pulaar / Pular).

- Used in all conjugations except the affirmative non-accomplished, where the long form is used instead.

See also

- aɗa (second person singular subject pronoun; long form), hiɗa (variant used in the Pular dialect of Futa Jalon)

- aan (emphatic form) (Maasina)

- an (emphatic form) (Pular)

- maaɗa (second person singular possessive pronoun (Adamawa))

- -maa (second person singular dependent pronoun (Adamawa))

Galician

Etymology 1

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- to, toward; indicating direction of motion

- introducing an indirect object

- used to indicate the time of an action

- (with de) to, until; used to indicate the end of a range

- de cinco a oito ― from five to eight

- by, on, by means of; expresses a mode of action

- a pé ― on foot

- for; indicates price or cost

Usage notes

The preposition a regularly forms contractions when it precedes the definite article o, a, os, and as. For example, a o ("to the") contracts to ao or ó, and a a ("to the") contracts to á.

Derived terms

| - | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | ao (ó) | aos (ós) |

| Feminine | á | ás |

Etymology 2

From Old Galician-Portuguese a, from Latin illa, feminine of ille (“that”).

Pronunciation

Article

a f (masculine singular o, feminine plural as, masculine plural os)

- (definite) the

Usage notes

The definite article o (in all its forms) regularly forms contractions when it follows the prepositions a (“to”), con (“with”), de (“of, from”), and en (“in”). For example, con a (“with the”) contracts to coa, and en a (“in the”) contracts to na.

Also, the definite article presents a second form that could be represented as <-lo/-la/-los/-las>, or either lack any specific representation. Its origin is in the assimilation of the last consonant of words ended in -s or -r, due to sandhi, with the /l/ present in the article in pre-Galician-Portuguese period. So Vou comer o caldo or Vou come-lo caldo are representations of /ˈβowˈkomelo̝ˈkaldo̝/ ("I'm going to have my soup"). This phenomenon, rare in Portuguese, is already documented in 13th century Medieval Galician texts, as the Cantigas de Santa Maria.[1]

Derived terms

Etymology 3

See the etymology of the corresponding lemma form.

Pronoun

a

- accusative of ela

Usage notes

Due to sandhi, the accusative form o (in all its forms) regularly changes to -lo after verbal forms ended in ⟨r⟩ or ⟨s⟩, and to -no after verbal forms ended in a semivowel:

- Eu apagueina 'I quenched it' < apaguei‿a

- Ti apagáchela 'You quenched it' < apagaches‿a

- El apagouna 'He quenched it' < apagou‿a

- Nós apagámola 'We quenched it' < apagamos‿a

- Temos de apagala 'We must quench it' < apagar‿a

References

- ^ Vaz Leão, Ângela (2000) “Questões de linguagem nas Cantigas de Santa Maria, de Afonso X”, in Scripta, volume 4, number 7, , retrieved 16 November 2017, pages 11-24

German

Etymology

Noun

a

- Abbreviation of a-Moll.

- Abbreviation of Ar.

Gilbertese

Etymology

From Proto-Oceanic *pat, from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *əpat, from Proto-Austronesian *Səpat.

Pronunciation

Numeral

a

Gothic

Romanization

a

- Romanization of 𐌰

Grass Koiari

Pronoun

a

- you (singular)

References

- 2010, Terry Crowley & Claire Bowern, An Introduction to Historical Linguistics, fourth edition, Oxford University Press, →ISBN, page 142.

Gun

Etymology

Pronunciation

Pronoun

à

- you (second-person singular subject pronoun)

See also

| Gungbe personal pronouns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Person | Emphatic Pronoun | Subject Pronoun | Object Pronoun | Possessive Determiner | |

| Singular | First | nyɛ́, yẹ́n | ùn, n | mi | cé, ṣié | |

| Second | jɛ̀, jẹ̀, yẹ̀, hiẹ̀ | à | wè | tòwè | ||

| Third | éɔ̀, úɔ̀, éwọ̀ | é | è | étɔ̀n, étọ̀n | ||

| Plural | First | mílɛ́, mílẹ́ | mí | mítɔ̀n, mítọ̀n | ||

| Second | mìlɛ́, mìlẹ́ | mì | mìtɔ̀n, mìtọ̀n | |||

| Third | yélɛ́, yélẹ́ | yé | yétɔ̀n, yétọ̀n | |||

Haitian Creole

Pronunciation

Article

a

Usage notes

This term only follows words that end with an oral (non-nasal) consonant and an oral vowel in that order, and can only modify singular nouns.

See also

Hawaiian

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a

Preposition

a

Usage notes

- Used for acquired possessions, while o is used for possessions that are inherited, out of personal control, and for things that can be got into (houses, clothes, cars).

Hokkien

| For pronunciation and definitions of a – see 阿. (This term is the pe̍h-ōe-jī form of 阿). |

Hungarian

Etymology 1

See az.

Pronunciation

Article

a (definite)

- the

- a hölgy ― the lady

- (before some time phrases) this

- a héten ― (during) this week

- a télen ― (in) this winter

Usage notes

Used before words starting with a consonant.

Related terms

- az (for words starting with a vowel sound)

Pronoun

a (demonstrative)

- (in reduplicated constructions formed with postpositions) that

- A mellett a ház mellett vártam rá. ― I waited for him/her next to that house.

Determiner

a (demonstrative)

- (rare, only in consonant-initial fixed phrases, with zero article) Alternative form of az (“that”).

- Foglalja össze, miről szóltak az a heti beszédek és leckék.[1] ― Summarize what that week’s sermons and lessons were about.

- November 12-én, az a havi frissítőkedden jelenhet meg. ― It may be released on November 12th, on the Patch Tuesday of that month.

- Kérjük szíves tájékoztatásukat a tekintetben, hogy… (= abban a tekintetben, see az) ― We kindly request your information in that [= the] aspect…

- amondó vagyok, hogy… ― I am of the opinion that…, what/all I can / want to say is that… (literally, “I am that-sayer/-saying…”)

References

Further reading

- a in Ittzés, Nóra (ed.). A magyar nyelv nagyszótára (’A Comprehensive Dictionary of the Hungarian Language’). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2006–2031 (work in progress; published A–ez as of 2021)

- Entries in Bárczi, Géza and László Országh. A magyar nyelv értelmező szótára (’The Explanatory Dictionary of the Hungarian Language’). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1959–1962. Fifth ed., 1992: ISBN 9630535793

Ido

Preposition

a

Related terms

Igbo

Etymology 1

Alternative forms

- e (neutral tongue position)

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a

- (indefinite) somebody, one, they, people (an unspecified individual).

- A gwara ya ka ọ bịa.

- He/she was told to come.

Usage notes

- Often gets translated into English with the passive voice.

See also

Etymology 2

Pronunciation

Determiner

a

- this.

Related terms

Indo-Portuguese

Etymology

From Portuguese a.

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- to

- 1883, Hugo Schuchardt, Kreolische Studien, volume 3 (overall work in German):

- […] , que da-cá su quião que ta pertencê a êll.

- , to give him his share which belongs to him.

Ingrian

Etymology

Pronunciation

- (Ala-Laukaa) IPA(key): /ˈthɑdhɑ/,

- (Soikkola) IPA(key): /ˈthɑdhɑ/,

- (Hevaha) IPA(key): /ˈɑ/,

- Rhymes: -ɑdh, -ɑdhɑ

Conjunction

a

- and, but

- 1936, N. A. Iljin and V. I. Junus, Bukvari iƶoroin șkouluja vart, Leningrad: Riikin Ucebno-pedagogiceskoi Izdateljstva, page 17:

- A siä Jaakko, kuhu määt?

- And you Jaakko, where are you going?

- 1936, L. G. Terehova, V. G. Erdeli, translated by Mihailov and P. I. Maksimov, Geografia: oppikirja iƶoroin alkușkoulun kolmatta klaassaa vart (ensimäine osa), Leningrad: Riikin Ucebno-Pedagogiceskoi Izdateljstva, page 7:

- keskipäivääl hää [päivyt] on kaikkiin ylemmääl, a siis alkaa laskiissa.

- on midday it is highest, and then it starts to descend.

References

- Ruben E. Nirvi (1971) Inkeroismurteiden Sanakirja, Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura, page 1

- Arvo Laanest (1997) Isuri keele Hevaha murde sõnastik, Eesti Keele Instituut, page 15

Interlingua

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

Derived terms

Inupiaq

Pronunciation

Interjection

a

Irish

Pronunciation

Etymology 1

From Old Irish a, from Proto-Celtic *esyo (the final vowel triggering lenition), feminine Proto-Celtic *esyās (the final -s triggering h-prothesis), plural Proto-Celtic *ēsom (the final nasal triggering eclipsis), all from the genitive forms of Proto-Indo-European *éy. Cognate with Welsh ei.

Determiner

a (triggers lenition)

- his, its

- a athair agus a mháthair ― his father and mother

- Chaill an t-éan a chleití.

- The bird lost its feathers.

Determiner

a (triggers h-prothesis)

- her, its

- a hathair agus a máthair ― her father and mother

- Bhris an mheaig a heiteog.

- The magpie broke its wing.

Determiner

a (triggers eclipsis)

- their

- a n-athair agus a máthair ― their father and mother

- a dtithe ― their houses

- a n-ainmneacha ― their names

- (Connacht) our

- (Connacht) your (plural)

See also

| Number | Person (and gender) | Conjunctive (emphatic) |

Disjunctive (emphatic) |

Possessive determiner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | First | mé (mise) |

mo L m' before vowel sounds | |

| Second | tú (tusa)1 |

thú (thusa) |

do L d' before vowel sounds | |

| Third masculine | sé (seisean) |

é (eisean) |

a L | |

| Third feminine | sí (sise) |

í (ise) |

a H | |

| Third neuter | — | ea | — | |

| Plural | First | muid, sinn (muidne, muide), (sinne) |

ár E | |

| Second | sibh (sibhse)1 |

bhur E | ||

| Third | siad (siadsan) |

iad (iadsan) |

a E | |

Determiner

a (triggers lenition)

- how (used with an abstract noun)

- A ghéire a labhair sí!

- How sharply she spoke!

- A fheabhas atá sé!

- How good it is!

Etymology 2

A reduced form of older do (itself a reanalysis of do used in past tenses, and also present in early modern verbs like do-bheirim (“I give”), do-chím (“I see”)), or from the preverb a- in early modern verbs like a-tú (“I am”), a-deirim (“I say”) in relative clauses.

Particle

a (triggers lenition except of d’ and of past autonomous forms)

- introduces a direct relative clause, takes the independent form of an irregular verb

- an fear a chuireann síol ― the man who sows seed

- an síol a chuireann an fear ― the seed that the man sows

- an síol a cuireadh ― the seed that was sown

- nuair a bhí mé óg ― when I was young

- an cat a d'ól an bainne ― the cat that drank the milk

References

Etymology 3

From Old Irish a (“that, which the relative particle used after prepositions”), reanalyzed as an independent indirect relative particle from forms like ar a (“on which, on whom”), dá (“to which, to whom”), or early modern le a (“with which, with whom”), agá (“at which, at whom”) when prepositional pronouns started to be repeated in such clauses (eg. don té agá mbíon cloidheamh (…) aige, daoine agá mbíonn grádh aco do Dhia). Compare the forms used in Munster instead: go (from agá (“at which”)) and na (from i n-a (“in which”), go n-a (“with which”), ria n-a (“before which”) and later lena (“with which”), tréna (“through which”)).

Particle

a (triggers eclipsis, takes the dependent form of an irregular verb; not used in the past tense except with some irregular verbs)

- introduces an indirect relative clause

- an bord a raibh leabhar air ― the table on which there was a book

- an fear a bhfuil a mhac ag imeacht ― the man whose son is going away

Related terms

- ar (used with the past tense of regular and some irregular verbs)

Pronoun

a (triggers eclipsis, takes the dependent form of an irregular verb; not used in the past tense except with some irregular verbs)

- all that, whatever

- Sin a bhfuil ann.

- That's all that is there.

- An bhfuair tú a raibh uait?

- Did you get all that you wanted?

- Íocfaidh mé as a gceannóidh tú.

- I will pay for whatever you buy.

Related terms

- ar (used with the past tense of regular and some irregular verbs)

References

- Nicholas Williams (1994) “Na Canúintí a Theacht chun Solais”, in K. McCone, D. McManus, C. Ó Háinle, N. Williams, L. Breatnach, editors, Stair na Gaeilge: in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish), Maynooth: Roinn na Sean-Ghaeilge, Coláiste Phádraig, →ISBN, page 464: “Tháinig nós chun cinn sa 17ú haois freisin an réamhfhocal a dhúbláil: don té agá mbíonn cloidheamh..aige; daoine agá mbíonn grádh aco do Dhia (Ó Cuív, 1952b, 177), an tí ag a bhfuil a bheag do chuntabhairt aige (Williams, 1986, 155).”

- Gerald O’Nolan (1934) The New Era Grammar of Modern Irish, The Educational Company of Ireland Ltd., page 56

Etymology 4

Particle

a (triggers lenition)

- introduces a vocative

- A Dhia!

- O God!

- A dhuine uasail!

- Sir!

- Tar isteach, a Sheáin.

- Come in, Seán.

- A amadáin!

- You fool!

Etymology 5

Particle

a (triggers h-prothesis)

- introduces a numeral

- a haon, a dó, a trí... ― one, two, three...

- Séamas a Dó ― James the Second

- bus a seacht ― bus seven

Etymology 6

Originally a reduced form of do.

Preposition

a (plus dative, triggers lenition)

- to (used with verbal nouns)

- síol a chur ― to sow seed

- uisce a ól ― to drink water

- an rud atá sé a scríobh ― what he is writing

- D’éirigh sé a chaint.

- He rose to speak.

- Téigh a chodladh.

- Go to sleep.

Mutation

| radical | eclipsis | with h-prothesis | with t-prothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | n-a | ha | not applicable |

Note: Certain mutated forms of some words can never occur in standard Modern Irish.

All possible mutated forms are displayed for convenience.

Further reading

- Ó Dónaill, Niall (1977) “Thadh/a”, in Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla, Dublin: An Gúm, →ISBN

- Gregory Toner, Sharon Arbuthnot, Máire Ní Mhaonaigh, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Dagmar Wodtko, editors (2019), “1 a (vocative particle)”, in eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language

- Gregory Toner, Sharon Arbuthnot, Máire Ní Mhaonaigh, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Dagmar Wodtko, editors (2019), “2 a (‘his, her, their’)”, in eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language

- Gregory Toner, Sharon Arbuthnot, Máire Ní Mhaonaigh, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Dagmar Wodtko, editors (2019), “3 a (particle used before numerals)”, in eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language

- Gregory Toner, Sharon Arbuthnot, Máire Ní Mhaonaigh, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Dagmar Wodtko, editors (2019), “4 a (‘that which’)”, in eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language

Istriot

Etymology

Preposition

a

- at

- 1877, Antonio Ive, Canti popolari istriani: raccolti a Rovigno, volume 5, Ermanno Loescher, page 99:

- A poûpa, a prùa a xì doûto bandere,

- At the stern, at the bow everything is flags,

- A poûpa, a prùa a xì doûto bandere,

- 1877, Antonio Ive, Canti popolari istriani: raccolti a Rovigno, volume 5, Ermanno Loescher, page 99:

Particle

a

- emphasises a verb; mandatory with impersonal verbs

- 1877, Antonio Ive, Canti popolari istriani: raccolti a Rovigno, volume 5, Ermanno Loescher, page 99:

- A poûpa, a prùa a xì doûto bandere,

- At the stern, at the bow everything is flags,

- A poûpa, a prùa a xì doûto bandere,

- 1877, Antonio Ive, Canti popolari istriani: raccolti a Rovigno, volume 5, Ermanno Loescher, page 99:

Italian

Pronunciation

Etymology 1

From Latin ad. In a few phrases, a stems from Latin ā, ab.

Preposition

a

- Indicates the indirect object. to

- Porta questo cesto alla nonna.

- Bring this basket to grandma.

- Ai gatti piacciono i pesci.

- Cats like fish.

- (literally, “Fish are pleasable to cats.”)

- E lo chiedi a me?

- You're asking that to me?

- Indicates the place, used in some contexts, in others in is used. in, to

- Andiamo a casa?

- Can we go home?

- (literally, “Can we go to home?”)

- Ora sto a Palermo, a Roma ci torno domani.

- I'm in Palermo now, I'll go back to Rome tomorrow.

- Denotes the manner. with

- Forms adverbs meaning “in a manner related or resembling ~”.

- a cappella, a bestia, a braccio, a pennello, etc. ― (please add an English translation of this usage example)

- Forms goodbye formulas from the time the persons will meet again. see you...

- A domani! ― See you tomorrow!

- A dopo! ― See you later!

- Al prossimo Natale! ― See you next Christmas!

- Introduces the ingredients of a dish, perfume, etc. with

- pasta all'uovo ― pasta with eggs

- cornetto al cioccolato ― chocolate croissant

- shampoo al limone ― lemon shampoo

- patatine alla pizza ― pizza-flavoured crisps

- (central-southern Italy) Denotes the direct object, but only if it's not preceded by articles

- Chiama a Paolo.

- Call Paolo.

- E non ci avevi visto a noi?

- And you didn't see us?

- Ascolti a me, signó!

- Listen to me, ma'am!

- (followed by the definite article) Forms an interjection that gives an instruction or calls attention to something.

- Al ladro! ― Thief!

- Al fuoco! ― Fire!

- Al lupo! ― Wolf!

- All'attacco! ― Attack!

- All'arrembaggio! ― Assault! (yelled by pirates)

- (regional) Forms continuous tense when preceded by stare and followed by verb infinitives. -ing. The standard language for this scope uses gerunds.

- che stai a di'? ― what are you saying?

- stavo a dormi' ― I was sleeping

- Repeated indicates the amount by which something grows. by

- a due a due ― two by two; in pairs

- a poco a poco ― little by little

- Indicates the agent of a verb in some contexts. by. Sometimes interchangable with da.

- L'ho sentito dire a Livia.

- I heard Livia say it.

- (literally, “I heard it said by Livia.”)

- c. 1909, Luigi Pirandello, chapter 2.3, in I vecchi e i giovani:

- Mi duole, creda, sinceramente, veder fare a un uomo come lei, per cui ho tanta stima, una figura... non bella, via! non bella.

- (please add an English translation of this quotation)

Usage notes

- When followed by a word that begins with a vowel sound, the form ad is used instead.

- When followed by the definite article, a combines with the article to produce the following combined forms:

a + article Combined form a + il al a + lo allo a + l' all' a + i ai a + gli agli a + la alla a + le alle

Descendants

- → Norwegian Bokmål: a (learned)

Etymology 2

Verb

a

- Misspelling of ha.

References

Further reading

- Thadh/a in Luciano Canepari, Dizionario di Pronuncia Italiana (DiPI)

Jamaican Creole

Preposition

a

- Indicates location: at, in, on.

- a mi yaad

- at my home

- of

- Yunaitid Stiet a Amoerka

- United States of America

- to

- Dem go a maakit. Mi a-go a skuul.

- They go to the market. I'm going to school.

Verb

a

Particle

a

- Habitual present tense marker.

- wan plies we dem a plie haki mach

- a place where they play hockey matches

- Precedes a verb to mark the -ing form.

- a laaf, a ron, a iit

- laughing, running, eating

See also

Further reading

- Thadh/a at majstro.com

- A Learner’s Grammar of Jamaican, The Open Grammar Project

Japanese

Romanization

a

K'iche'

Pronunciation

Adjective

a

- masculine youth indicator

Adverb

a

- (interrogatory) indicator of a question

Pronoun

a

- your

References

- Allen J. Christenson, Kʼiche-English dictionary, page 7

Kabyle

Alternative forms

Determiner

a

- this

- a rgaz a

- this man

Kalasha

Etymology

Pronoun

a (Arabic آ)

- I (1st-person personal pronoun)

See also

Kapampangan

Ligature

a

- connects adjectives to nouns

- Romantiku a bengi.

- A romantic night.

- Pinakapalsintan a tau.

- The person I love the most.

- Mayap a abak.

- Good morning.

- Mayap a bengi.

- Good night.

- Dakal a salamat.

- Thank you very much.

See also

Kari'na

Pronunciation

Interjection

a

References

- Courtz, Hendrik (2008) A Carib grammar and dictionary, Toronto: Magoria Books, →ISBN, page 213

- Yamada, Racquel-María (2010) “a”, in Speech community-based documentation, description, and revitalization: Kari’nja in Konomerume, University of Oregon, page 707

Kashubian

Pronunciation

- Template:csb-IPA

- Syllabification: a

Etymology 1

Noun

a n (indeclinable)

Etymology 2

Inherited from Proto-Slavic *a.

Conjunction

a

- and (used to continue a previous statement or to add to it)

Etymology 3

Inherited from Proto-Slavic *a.

Interjection

a

- interjection that expresses various emotions; ah!

Further reading

- Stefan Ramułt (1893) “Thadh/a”, in Słownik języka pomorskiego czyli kaszubskiego (in Kashubian), page 1

- Sychta, Bernard (1967) “a, a!”, in Słownik gwar kaszubskich [Dictionary of Kashubian dialects] (in Polish), volumes 1 (A – Ǵ), Wrocław: Ossolineum, page 1

- Eùgeniusz Gòłąbk (2011) “Thadh/a”, in Słownik Polsko-Kaszubski / Słowôrz Pòlskò-Kaszëbsczi, volume 1, page 9

- “A, a”, in Internetowi Słowôrz Kaszëbsczégò Jãzëka [Internet Dictionary of the Kashubian Language], Fundacja Kaszuby, 2022

- “a!”, in Internetowi Słowôrz Kaszëbsczégò Jãzëka [Internet Dictionary of the Kashubian Language], Fundacja Kaszuby, 2022

Koitabu

Pronoun

a

- you (singular)

References

- Terry Crowley, Claire Bowern, An Introduction to Historical Linguistics

Krisa

Pronunciation

Noun

a m

- pig

- Nana a doma.

- I shot your pig.

References

- Donohue, Mark and San Roque, Lila. I'saka: a sketch grammar of a language of north-central New Guinea. (Pacific Linguistics, 554.) (2004).

Ladin

Etymology

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

Derived terms

Lashi

Pronunciation

Adverb

a

References

Latgalian

Etymology

Ultimately from Proto-Balto-Slavic *ō. The source is not clear:

- Probably borrowed from a Slavic language (compare Russian а (a) and Belarusian а (a)).

- Alternatively, irregularly shortened from *ā, inherited from *ō.

Compare Lithuanian o.

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a f

References

- A. Andronov, L. Leikuma (2008) Latgalīšu-Latvīšu-Krīvu sarunu vuordineica, Lvava, →ISBN

Latin

Etymology 1

Alternative form of ab by apocope (not used before a vowel or h).

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Preposition

ā (+ ablative)

- (indicating ablation) from, away from, out of

- c. 52 BCE, Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.1:

- Gallōs ab Aquītānīs Garumna flūmen, ā Belgīs Matrona et Sēquana dīvidit.

- The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the Marne and the Seine (separate them) from the Belgae.

- Gallōs ab Aquītānīs Garumna flūmen, ā Belgīs Matrona et Sēquana dīvidit.

- (indicating ablation) down from

- (indicating agency: source of action or event) by, by means of

- 45 BCE, Cicero, De finibus bonorum et malorum 1.2:

- Quamquam philosophiae quidem vituperātōribus satis respōnsum est eō librō, quō ā nōbīs philosophia dēfēnsa et collaudāta est, cum esset accūsāta et vituperāta ab Hortēnsiō.

- Although indeed to the vituperators of philosophy an adequate response is in that book, in which philosophy has been defended and highly praised by us , when it had been accused and vituperated by Hortensius.

- Quamquam philosophiae quidem vituperātōribus satis respōnsum est eō librō, quō ā nōbīs philosophia dēfēnsa et collaudāta est, cum esset accūsāta et vituperāta ab Hortēnsiō.

- (indicating instrumentality: source of action or event) by, by means of, with

- (indicating association) to, with

- 163 BCE, Publius Terentius Afer, Heauton Timorumenos 1.77:

- Homō sum, hūmānī nihil ā mē aliēnum putō.

- I am a man; I consider nothing that is human alien to me.

- Homō sum, hūmānī nihil ā mē aliēnum putō.

- (indicating location) at, on, in

- (time) after, since

Usage notes

Used in conjunction with passive verbs to mark the agent.

- Liber ā discipulō aperītur.

- The book is opened by the student.

Derived terms

Descendants

Etymology 2

Expressive.

Pronunciation

Interjection

ā

Further reading

- “Thadh/a”, in Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short (1879) A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- “Thadh/a”, in Charlton T. Lewis (1891) An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York: Harper & Brothers

- Thadh/a in Gaffiot, Félix (1934) Dictionnaire illustré latin-français, Hachette.

- “Thadh/a”, in ΛΟΓΕΙΟΝ Dictionaries for Ancient Greek and Latin (in English, French, Spanish, German, Dutch and Chinese), University of Chicago, since 2011

Laz

Determiner

a

- Latin spelling of ა (a)

Numeral

a

- Latin spelling of ა (a)

Ligurian

Pronunciation

Etymology 1

| Ligurian Definite Articles | ||

|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | |

| masculine | o | i |

| feminine | a | e |

Article

a f sg (plural e)

Etymology 2

Preposition

a

- in

- at

- to

- Vàddo a câza. ― I'm going home. (literally, “I go to home.”)

- indicates the direct object, mainly to avoid confusion when it, the subject, or both are displaced, or for emphasis

- A mæ seu ghe fa mâ 'n bràsso. ― My sister's arm hurts. (literally, “To my sister an arm hurts.”)

Louisiana Creole

Etymology

From French avoir (“to have”).

Verb

a

- to have

Lower Sorbian

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a

Further reading

- Muka, Arnošt (1921, 1928) “Thadh/a”, in Słownik dolnoserbskeje rěcy a jeje narěcow (in German), St. Petersburg, Prague: ОРЯС РАН, ČAVU; Reprinted Bautzen: Domowina-Verlag, 2008

- Starosta, Manfred (1999) “Thadh/a”, in Dolnoserbsko-nimski słownik / Niedersorbisch-deutsches Wörterbuch (in German), Bautzen: Domowina-Verlag

Malay

Pronunciation

Interjection

a (Jawi spelling ا)

- Used to show excitement or to show agreement.

- A, macam itulah sepatutnya kaujawab!

- Yes, that's how you should answer!

- Used to show that you have forgotten or are attempting to remember something.

- Dia ni, a, salah seorang Perdana Menteri Britain dulu.

- This guy is, uh, one of Britain's Prime Ministers in the past.

Further reading

- “Thadh/a” in Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu | Malay Literary Reference Centre, Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2017.

Mandarin

Romanization

a (Zhuyin tha dh/a)

- Hanyu Pinyin reading of 呵

- Hanyu Pinyin reading of 啊

- Hanyu Pinyin reading of 阿

a

- Nonstandard spelling of ā.

- Nonstandard spelling of á.

- Nonstandard spelling of ǎ.

- Nonstandard spelling of à.

Usage notes

- Transcriptions of Mandarin into the Latin script often do not distinguish between the critical tonal differences employed in the Mandarin language, using words such as this one without indication of tone.

Mandinka

Pronoun

a

- he, him (personal pronoun)

- A m busa ― He/she struck me.

- Y a busa ― They struck him/her.

- she, her (personal pronoun)

- it (personal pronoun)

See also

Maori

Particle

a

Usage notes

- When used in the sense of of, suggests that the possessor has control of the relationship (alienable possession).

Mezquital Otomi

Etymology 1

Pronunciation

Interjection

a

- expresses satisfaction, pity, fright, or admiration

Etymology 2

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Verb

a

- (transitive) wake, awaken

Etymology 3

From Proto-Otomi *ʔɔ, from Proto-Otomian *ʔɔ.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Noun

a

Derived terms

References

- Andrews, Enriqueta (1950) Vocabulario otomí de Tasquillo, Hidalgo (in Spanish), México, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, page 1

- Hernández Cruz, Luis, Victoria Torquemada, Moisés (2010) Diccionario del hñähñu (otomí) del Valle del Mezquital, estado de Hidalgo (Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas “Mariano Silva y Aceves”; 45) (in Spanish), second edition, Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C., page 3

Middle Dutch

Etymology

From Old Dutch ā, from Proto-Germanic *ahwō.

Noun

â f

Inflection

This noun needs an inflection-table template.

Descendants

Further reading

- “Thadh/a (II)”, in Vroegmiddelnederlands Woordenboek, 2000

Middle English

Etymology 1

Pronoun

a

- Alternative form of an (mainly preconsonantal)

Etymology 2

Pronoun

a

- (Late Middle English) Alternative form of I (“I”)

Etymology 3

Pronoun

a

- Alternative form of heo (“she”)

Etymology 4

Pronoun

a

- Alternative form of he (“he”)

Etymology 5

Pronoun

a

- Alternative form of he (“they”)

Etymology 6

Numeral

a

- (Northern, Early Middle English) Alternative form of oo (“one”)

Middle French

Etymology 1

From Old French a, from Latin ad.

Alternative forms

- à (after 1550)

Preposition

a

Etymology 2

From Old French, from Latin habet.

Verb

a

Middle Welsh

Etymology 1

Pronunciation

Particle

a (triggers lenition)

- O (vocative particle)

Etymology 2

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a (triggers lenition)

Particle

a (triggers lenition)

- inserted before the verb when the subject of direct object precedes it

Etymology 3

Pronunciation

Particle

a (triggers lenition)

- used to introduce a direct question

- whether, used to introduce an indirect question

Etymology 4

Reduction of o (“from”).

Pronunciation

Preposition

a

- used between a focused adjective and the noun it modifies

- Pwyll Pendeuic Dyuet:

- bychan a dial oed yn lloski ni, neu yn dienydyaw am y mab

- (please add an English translation of this quotation)

- it will be small vengeance if we are burnt or put to death because of the child

- Pwyll Pendeuic Dyuet:

Etymology 5

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Conjunction

a (triggers aspiration)

Etymology 6

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Preposition

a (triggers aspiration)

Etymology 7

From Proto-Celtic *ageti, from Proto-Indo-European *h₂eǵ-.

Alternative forms

Pronunciation

Verb

a

Mutation

| radical | soft | nasal | h-prothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | unchanged | unchanged | ha |

Note: Certain mutated forms of some words can never occur in standard Middle Welsh.

All possible mutated forms are displayed for convenience.

Mòcheno

Etymology

From Middle High German ein, from Old High German ein, from Proto-West Germanic *ain, from Proto-Germanic *ainaz (“one, a”).

Article

a (oblique masculine an)

References

- “Thadh/a” in Cimbrian, Ladin, Mòcheno: Getting to know 3 peoples. 2015. Servizio minoranze linguistiche locali della Provincia autonoma di Trento, Trento, Italy.

Mopan Maya

Article

a

References

- Hofling, Charles Andrew (2011). Mopan Maya–Spanish–English Dictionary, University of Utah Press.

Mountain Koiari

Pronoun

a

- you (singular)

References

- Terry Crowley, Claire Bowern, An Introduction to Historical Linguistics

Murui Huitoto

Adverb

a

References

- Shirley Burtch (1983) Diccionario Huitoto Murui (Tomo I) (Linguistica Peruana No. 20) (in Spanish), Yarinacocha, Peru: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, page 19

Nauruan

Pronunciation

Pronoun

a

- I (first person singular pronoun)

- 2000, Lisa M Johnson, Firstness of Secondness in Nauruan Morphology (overall work in English):

- a pudun

- 1sing fall+Vn

I fell

- 1sing fall+Vn

- a nuwawen

- 1pers.sing. go+Vn

I did go. (I left.)

- 1pers.sing. go+Vn

- a kaiotien aem

-

I hear what you said.

-

- a nan imoren

- 1pers.sing. FUT health+Vn

I shall be cured (get better).

- 1pers.sing. FUT health+Vn

Neapolitan

Pronunciation

Etymology 1

Preposition

a

Etymology 2

Preposition

a

- in (locative: staying in a place of relative width)

- to (locative: moving towards a place of relative width)

- to (dative)

Nias

Etymology

From Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *kaən, from Proto-Austronesian *kaən.

Verb

a (imperfective manga)

- (transitive) to eat

References

- Sundermann, Heinrich. 1905. Niassisch-deutsches Wörterbuch. Moers: Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, p. 15.

Norman

Verb

a

Norwegian Bokmål

Etymology 1

From Latin a, from Ancient Greek Α (A, “alpha”), likely through the Etruscan language, from Phoenician 𐤀 (ʾ), from Proto-Canaanite ![]() , from Proto-Sinaitic

, from Proto-Sinaitic ![]() , from Egyptian 𓃾, representing the head of an ox.

, from Egyptian 𓃾, representing the head of an ox.

Pronunciation

Noun

a m (definite singular a-en, indefinite plural a-er, definite plural a-ene)

- indicates the first or best entry of a list, order or rank

- Synonyms: A-, a-

- oppgang A ― apartment entrance A

- blodgruppe A ― blood group A

- førerkort i klasse A ― (motorcycle) driver's license in class A

- øl i klasse A ― beer in class A (with 0,0-0,7 volume percent alcohol)

- A post ― A post / priority mail

- A-aksje ― class A-share

- hepatitt A ― hepatitis A

- 1919, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Samlede digter-verker I [Collected poetic works 1], page 454:

- [bokstavene begynte] at gaa sammen, to og to: a stod og hvilte under et træ, som hedte b

- to go together, two by two: a stood and rested under a tree called b

- 1920, Jonas Lie, Samlede Digterverker V, page 389:

- begynde paa Ø istedet for A

- start with Ø instead of A

- 1886, Arne Garborg, Mogning og manndom I, page 172:

- jeg traf sammen med et par generalbanditter, gamle gutter, storartede ranglefanter, 1ste klasse 1 A med stjerne, deilige herremænd

- I met a couple of general bandits, old boys, great revelers, 1st class 1 A with a star, lovely gentlemen

- 1939, Knut Hamsun, Artikler, page 99:

- historie er hvad A mener til forskel fra B, og hvad C igen mener til forskel baade fra A og B om den samme sag

- story is what A thinks differently from B and what C again thinks differently from both A and B about the same case

- the highest grade in a school or university using the A-F scale

- få A til eksamen

- receive an A on an exam

- 2019, Helene Uri, Stillheten etterpå, page 14:

- jeg har gode karakterer. Bare A-er og B-er

- I have good grades. Only A's and B's

- (music) designation of the sixth note from C and the corresponding tone

- 1944, Børre Qvamme, Musikk, page 10:

- synge en riktig A uten hjelp av et instrument eller stemmegaffel

- sing a correct A without the aid of an instrument or tuning fork

- 1973, Finn Havrevold, Avreisen, page 127:

- han slår énstrøken a på klaveret

- he strikes one stroke A on the piano

- 1997, Tove Nilsen, G for Georg, page 42:

- så gal at man virkelig tror at svaler er g-nøkler og bass-nøkler og a’er og c’er som svever rundt hverandre og lager konsert i himmelen

- so crazy that you really think swallows are g-keys and bass-keys and a's and c's floating around each other and making a concert in the sky

- (physics) symbol for ampere

- (physics) symbol for nucleon number

- (horology) symbol for avance

- symbol for anno

- short form of atom-

- Synonym: a-

- a-bombe

- atom bomb (a-bomb)

Derived terms

- a-form (“a-form”), a-infinitiv (“a-infinitive”), a-kjendis (“A-list celebrity”)

Etymology 2

Abbreviation of atto- (“atto-”).

Symbol

a

- atto-, prefix for 10-18 in the International System of Units.

Etymology 3

Abbreviation of ar (“are”).

Symbol

a

Etymology 4

Preposition

a

- Alternative spelling of à

Alternative forms

Etymology 5

From Latin ā (“from, away from, out of”), alternative form of ab (“from, away from, out of, down from”).

Preposition

a

Alternative forms

Etymology 6

From Italian a (“in, at, to”).

Preposition

a

Etymology 7

From Old Norse hana (“her”), accusative form of hón (“she”), from Proto-Norse (*hān-), from a prefixed form of Proto-Germanic *ainaz (“one; some”), from Proto-Indo-European *óynos (“one; single”).

Pronoun

a

- (dialectal, used enclitically after a conjunction or subjunction) she

- 1948, Helge Krog, Skuespill I, page 43:

- jagu slår a ja. Og det så det kjens. Forleden dag ga hun meg en knallende ørefik

- she can certainly punch. And so you feel it. The other day she gave me a popping slap to the ear

- 1989, Bergljot Hobæk Haff, Den guddommelige tragedie:

- hu kunne ikke henge på seg så mye som et enrada perlebånd, uten at a måtte skotte opp i skyene for å høre hva den aller høyeste mente

- she could not put on as much as a single string of pearls, without having to shoot up into the clouds to hear what the very highest one meant

- (dialectal, about grammatically feminine animals or objects) it, she

- 1899, Sfinx, Vi og Voreses, page 45:

- hos Hansens laa dem te klokka var ni, og 10 var a mange ganger ogsaa

- at Hansen's they laid until nine o'clock, and 10 she was many times too

- 1954, Agnar Mykle, Lasso rundt fru Luna, page 476:

- hvor ligger a henne?

- where is the hat?

- hvor er a katta di?

- where is your cat?

- Synonym: hun

- (dialectal, used enclitically) her; object form of hun (=she)

- hva gjorde du med a?

- what did you do to her?

- 1847–1868, Halfdan Kjerulf, Av hans efterladte papirer, page 245:

- jeg klaverstykker … en lille scherzo med nordisk motiv … «gjenta» og «Jørgen Matros», som gjør kur til ’a og «Ola Spelman» som hun foretrækker

- I piano pieces… a small scherzo with a Nordic motif… «gjenta» and «Jørgen Matros», which makes cure for her and «Ola Spelman» which she prefers

- 1875, Alexander Erbe, Fra skjærgaarden, page 23:

- skulle da koste paa a amen

- would then cost her amen

- 1921, Sigrid Undset, Samlede romaner og fortællinger fra nutiden I, page 6:

- jeg kan da gjerne skjære litt mat til a

- I could happily cut some food for her

- 1931, Aksel Sandemose, En sjømann går i land, page 19:

- han stakk henne med kniven, riktig kylt’n midt i magan på a

- he stabbed her with the knife, really threw in the middle of her stomach

- 2010, Helene Guåker, Kjør!:

- flere enn deg i hvert fall, di lørje, svarte jeg og så a midt i aua

- more than you at least, you skank, I answered and looked her in the eye

- hva gjorde du med a?

- (dialectal, about grammatically feminine animals or objects) it, her

- hvis katta stikker av, må du fange a!

- if the cat runs away, you need to catch her!

- 1895, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Over Ævne II, page 136:

- naar kjærka ikke kan holde arbejderne i ave , aa faen skal vi saa me’a

- when the church can not keep the workers in duty, what the hell do we do with her then

- Synonym: henne

- hvis katta stikker av, må du fange a!

- (dialectal, used proclitically with a woman's name or female relation) she, her

- 1921, Sigrid Undset, Samlede romaner og fortællinger fra nutiden V, page 96:

- ta a Guldborg

- consider Guldborg

- 1921, Sigrid Undset, Samlede romaner og fortællinger fra nutiden V, page 64:

- har du glemt a mamma

- did you forget about mom

- 2015, Rudolf Nilsen, Samlede dikt, page 88:

- a Paula kom plystrende hjem

- Paula came home whistling

- 2015 March 12, Gerd Nyland, “Fire år uten radio”, in Oppland Arbeiderblad, archived from the original on 2023-01-28:

- a tante Karen, mor hennes Reidun, hadde ordne med sengeplasser i stua, Booken på en divan og a Rita på flatseng på golvet

- aunt Karen, her mother Reidun, had arranged beds in the living room, Booken on a daybed and Rita on a flat bed on the floor

Etymology 8

From Danish ah (“oh”), likely from German ach (“oh”), from Middle High German ach, from Old High German ah. Also see ah and akk.

Interjection

a

- expression of surprise or horror

- a, for noe tøv!

- oh, such nonsense!

- 1888, Herman Colditz, Kjærka, et Atélierinteriør:

- a, det er bare noe drit til han terracottaen

- oh, that is just some crap for that terracotta guy

- expression of admiration or happiness

- a, det gjorde godt!

- oh, that felt good!

- 1897, Fridtjof Nansen, Fram over Polhavet I, page 345:

- a, kunde vi bare gi «Fram» slige vinger

- oh, if only we could give "Fram" wings like that

- used with the words yes and no to give a sense of impatience or rejection

- a jo, men hold nå fred!

- oh yes, but keep quiet now

- 1874, Henrik Ibsen, Fru Inger til Østråt, page 99:

- a nej, det kan være det samme

- oh no, it does not matter

- 1874-1878, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Brytnings-år I, page 25:

- a ja, lad Schirmer tegne staburet

- oh yes, let Schirmer draw the storehouse

- 1988, Arild Nyquist, Giacomettis forunderlige reise:

- verden er vakker, bestemor. Selv når det regner og blåser. A ja da.

- the world is beautiful, grandma. Even when it's raining and windy. Oh yes.

Etymology 9

Mostly likely from Norwegian ad (“against, on”), from Danish ad (“by, at”), from Old Danish at, from Old Norse at (“at, to”), from Proto-Germanic *at (“at, toward, to”), from Proto-Indo-European *h₂éd (“to, at”).

Interjection

a

- expression of anger or sorrow, especially with a personal pronoun

- uff a meg!

- oh, my!

- huff a meg!